PHIL 332, Philosophy of Beauty, Additions

Contents

1.

Descriptions of beauties and of the effect of beauty

1.

Salman Rushdie, Fury, excerpt

2.

John Ruskin describing a day high in

the Alps

3.

Dylan Thomas, "Poem in

October," excerpt

4.

Jean Dubuffet on things

traditionally despised as "unaesthetic": Empreintes.

5.

Sarah Hubbell on the beauty of

insects

6.

The Japanese Wabi-sabi

aesthetic

7.

A consolingly beautiful feature in a

corpulent, aged body

8.

A truly beautiful state of mind:

Patrick Leigh Fermor

2.

The Neoplatonic

impulse to ascend to Beauty Itself as inherent to aesthetic experience and Kirwan's phenomenological version of this.

3.

James Kirwan's

idea of a Neoplatonic-like yearning lying within our

experience of beauty

4.

Mathematical beauty in art forms:

images and texts from Ivar Peterson, Fragments of

Infinity.

5.

Kenneth Chang, "What makes an

equation beautiful." NY Times, 10/24/04.

6.

Jonathan Swift on the Laputans' obsession with mathematically regular forms, from

Gulliver's Travels, 1729.

7.

Hutcheson's application of the

uniformity and variety criterion to geometry and astronomy

8.

Modes of Apollonian and Dionysian

architecture

1.

Classical Greek temples

2.

Gothic and Hindu temples

3.

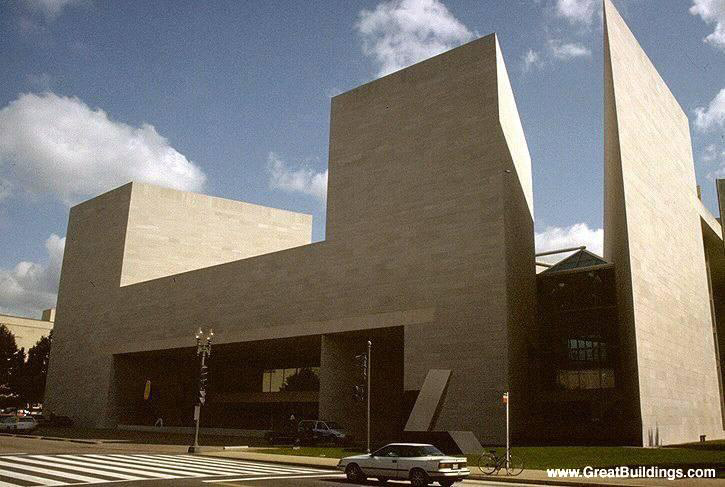

Cool modernism: I. M. Pei's National

Gallery East wing.

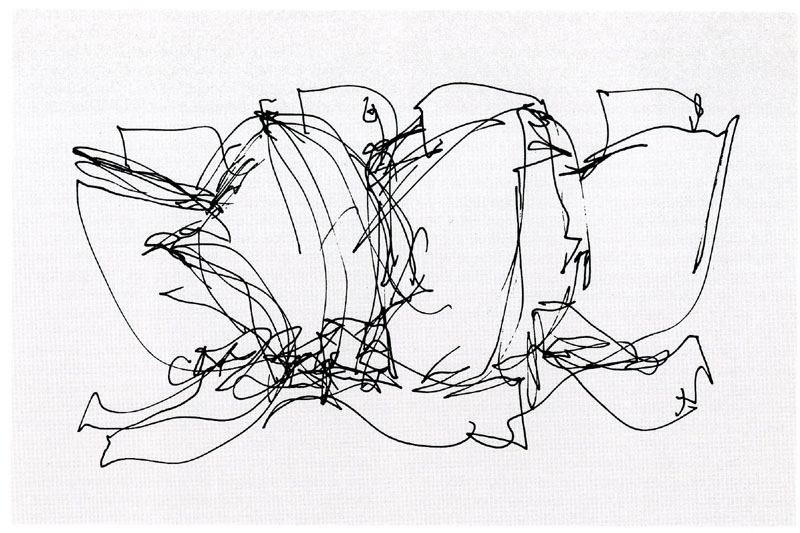

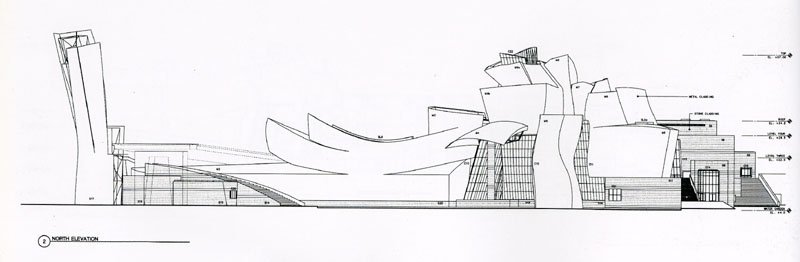

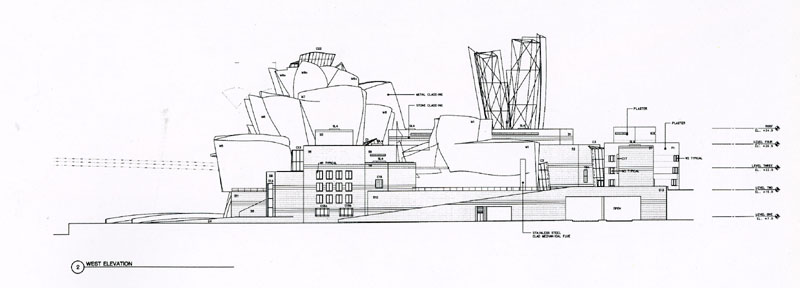

4.

Post-modernist free-flow

architecture: Frank Gehry Guggenheim Bilbao

9.

Other illustrations re. Apollonian

vs. Dionysian beauty

10. Scent and

flavor as an art form: Karl Joris Huysmans' decadent

aesthete, Des Esseintes.

11. Properties

of scent

1.

Odor descriptions of fragrant oils

2.

Odor classification

3.

A code for smell

4.

Creative development of perfumes of

a given type

5.

The Malororous

garden

12. Psychological

investigation into the common properties of faces widely judged beautiful, the

connection between beauty and evolutionary survival, etc.

1.

Beauty and the beholder, Nature,

3/17/94

2.

Facial beauty and the golden

section: the Marquardt beauty mask

13. Mate choice

as influencing human development: Geoffrey F. Miller (1998)

14. Variations

in ideals of the human body

15. Jonathan

Swift on the Houyhnhnms, from Gullivers'

Travels (1729)

16. Edward Bullough, "Psychical Distance as a Factor in Art and

an Aesthetic Principle," excerpt.

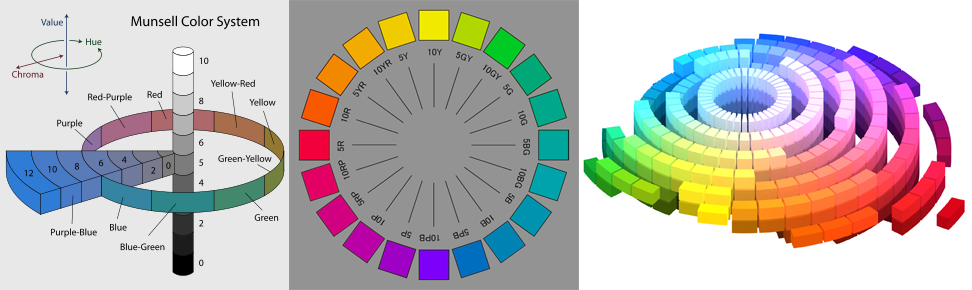

17. Munsell Color Solid

18. Beautiful

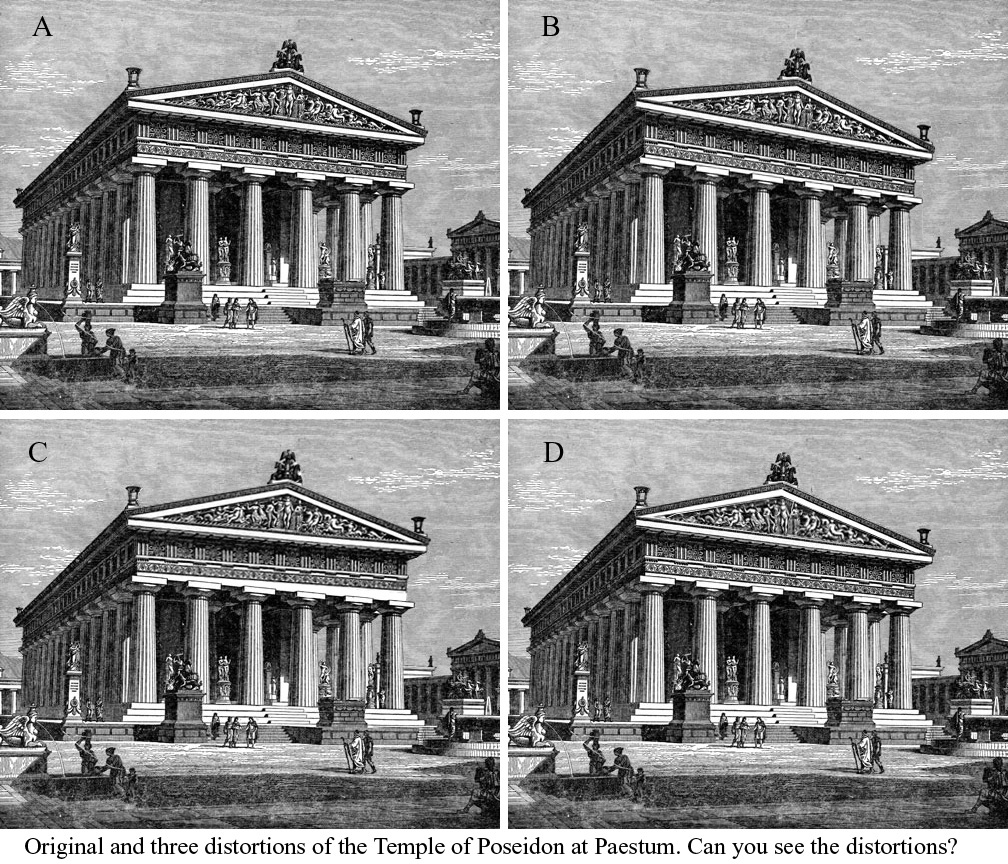

regularity and appearances of regularity/irregularity. Temple of Poseidon at

Paestum and three modifications. Homework exercise.

a. Perception of

differences

b. Aesthetic appreciation

of differences

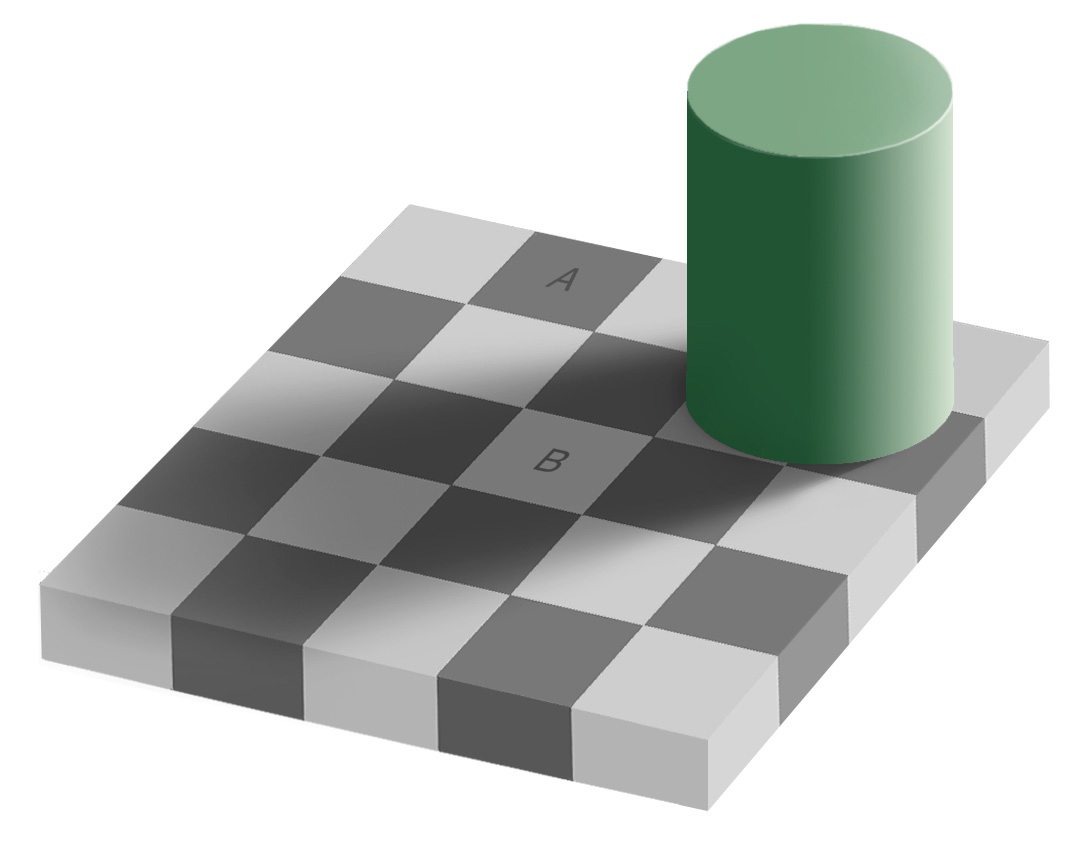

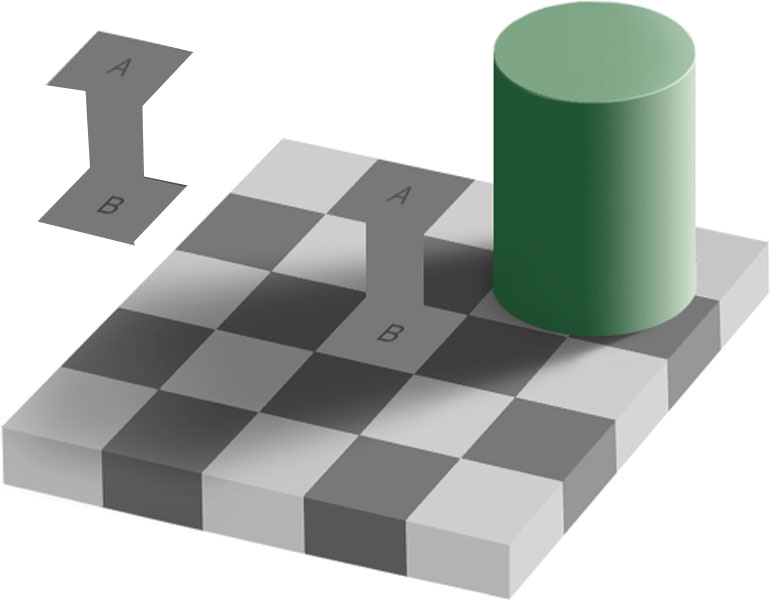

19. An

unbreakable visual illusion

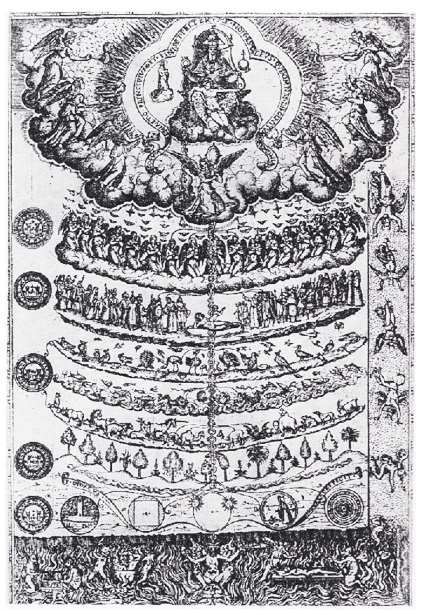

20. Great chain

of being illustration.

21. The

aesthetic character of athletic mastery

22. Amazing

pendulum movements.

23. George

Bernard Shaw on the pleasures of heaven and hell, Man and Superman, Act

III.

*****************************************

1. Descriptions of beauties and of the

effect of beauty.

1.1. Salman Rushdie, Fury (2002) describes the effect of a beautiful young woman of

mixed Polynesian and Indian parentage. The protagonist of the novel, himself

dazzled from an earlier meeting at her boyfriend's apartment, meets her on the

steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue. They sit for a while

and then start walking on Fifth Avenue.

Neela was wearing a knee-length mustard-colored scarf dress in silk. Her black hair was twisted up into a tight chignon and her long arms were bare. A cab stopped and expelled its passenger just in case she needed a ride, A hot dog vender offered her anything she wanted, free of charge. "just eat it here, lady, so I can watch you do it." ...Solanka felt as if he were escorting one of the Met's more important possessions down an awestruck Fifth Avenue. No: the masterpiece he was thinking of was at the Louvre. With a light breeze flowing the dress against her body, she looked like the Winged Victory of Samothraki, only with the head on... (147)

They walk into Central Park:

They sat on a bench near the pond, and all around them dog walkers were colliding with trees, Tai Chi practitioners lost their balance, rollerbladers smashed into one another, and people out strolling just walked right into the pond as if they'd forgotten it was there. Neela Mahendra gave no sign of noticing any of this. A man walded past with an ice cream cone, which, owing to his sudden but comprehensive loss of hand-to-mouth coordination, completely missed his tongue and instead made contact, messily, with his ear. Another young fellow began, with every appearance of genuine emotion, to weep copiously as he jogged by...(149)

Much later she talks about herself. (204-5)

She spoke of her beauty as something a little separate from herself. It had simply "shown up." It wasn't the result of anything she'd done. She took no credit for it, was grateful for the gift she'd been given, took great care of it, but mostly thought of herself as a disembodied entity living behind the eyes of this extraordinary alien, her body: looking out through its large eyes, manipulating its long limbs, not quite able to believe her luck. Her impact on her surroundings — the fallen window cleaners sitting splay-legged on various sidewalks with buckets on their heads, the skidding cars, the danger to cleaver-wielding butchers when she stopped for meat – was a phenomenon of whose results, for all her apparent unconcern, she was sharply, precisely aware. She could control "the effect" to some degree...she could intensify the world's response to her by making fine-tuning adjustments to her stride length, the tilt of her chin, her mouth, her voice. At maximum intensity she threatened to reduce entire precincts to disaster zones.

1.2. John Ruskin describing a day high in

the Alps

From Modern Painters (1873), Vol.

1, Section III, Chapter IV, "Of Truth of Clouds," ##35-37.

Ruskin's purpose is to contrast clouds as

they really are with the poor efforts of traditional painters, and to describe

how superior the clouds in J.M.Turner's works are,

but I have deleted references of this sort. All that matters for our purposes

are the description Ruskin gives and the manifest effect the beauties he

witnesses have on him.

§ 35. Morning on the plains

...Stand upon the peak of some isolated mountain at daybreak, when the night mists first rise from off the plains, and watch their white and lake-like fields as they float in level bays and winding gulfs about the islanded summits of the lower hills, untouched yet by more than dawn, colder and more quiet than a windless sea under the moon of midnight; watch when the first sunbeam is sent upon the silver channels, how the foam of their undulating surface parts and passes away; and down, under their depths, the glittering city and green pasture lie like Atlantis, between the white paths of winding rivers; the flakes of light falling every moment faster and broader among the starry spires, as the wreathed surges break and vanish above them, and the confused crests and ridges of the dark hills shorten their gray shadows upon the plain...

§ 36. Noon with

gathering storms.

Wait a little longer, and you shall see those scattered mists rallying in the ravines, and floating up toward you, along the winding valleys, till they couch in quiet masses, iridescent with the morning light,* upon the broad breasts of the higher hills, whose leagues of massy undulation will melt back and back into that robe of material light, until they fade away, lost in its lustre, to appear again above, in the serene heaven, like a wild, bright, impossible dream, foundationless and inaccessible, their very bases vanishing in the unsubstantial and mocking blue of the deep lake below...Wait yet a little longer, and you shall see those mists gather themselves into white towers, and stand like fortresses along the promontories, massy and motionless, only piled with every instant higher and higher into the sky, and casting longer shadows athwart the rocks; and out of the pale blue of the horizon you will see forming and advancing a troop of narrow, dark, pointed vapors, which will cover the sky, inch by inch, with their gray network, and take the light off the landscape with an eclipse which will stop the singing of the birds and the motion of the leaves together; and then you will see horizontal bars of black shadow forming under them, and lurid wreaths create themselves, you know not how, along the shoulders of the hills; you never see them form, but when you look back to a place which was clear an instant ago, there is a cloud on it, hanging by the precipices, as a hawk pauses over his prey...And then you will hear the sudden rush of the awakened wind, and you will see those watch-towers of vapor swept away from their foundations, and waving curtains of opaque rain let down to the valleys, swinging from the burdened clouds in black, bending fringes, or pacing in pale columns along the lake level, grazing its surface into foam as they go.

§ 37. Sunset in tempest.

Serene midnight.

And then; as the sun sinks, you shall see the storm drift for an instant from off the hills, leaving their broad sides smoking, and loaded yet with snow-white torn, steam-like rags of capricious vapor, now gone, now gathered again; while the smouldering sun, seeming not far away, but burning like a red-hot ball beside you, and as if you could reach it, plunges through the rushing wind and rolling cloud with headlong fall, as if it meant to rise no more, dyeing all the air about it with blood... And then you shall hear the fainting tempest die in the hollow of the night, and you shall see a green halo kindling on the summit of the eastern hills, brighter -- brighter yet, till the large white circle of the slow moon is lifted up among the barred clouds, step by step, line by line; star after star she quenches with her kindling light, setting in their stead an army of pale, penetrable, fleecy wreaths in the heaven, to give light upon the earth, which move together, hand in hand, company by company, troop by troop, so measured in their unity of motion, that the whole heaven seems to roll with them, and the earth to reel under them...

§ 38. And sunrise on the Alps

And then wait yet for one hour, until the east again becomes purple,* and the heaving mountains, rolling against it in darkness, like waves of a wild sea, are drowned one by one in the glory of its burning; watch the white glaciers blaze in their winding paths about the mountains, like mighty serpents with scales of fire; watch the columnar peaks of solitary snow, kindling downwards, chasm by chasm, each in itself a new morning; their long avalanches cast down in keen streams brighter than the lightning, sending each his tribute of driven snow, like altar-smoke, up to the heaven; the rose-light of their silent domes flushing that heaven about them and above them, piercing with purer light through its purple lines of lifted cloud, casting a new glory on every wreath as it passes by, until the whole heaven -- one scarlet canopy, -- is interwoven with a roof of waving flame, and tossing, vault beyond vault, as with the drifted wings of many companies of angels; ...

* I have often seen the white, thin, morning cloud, edged with the seven colors of the prism. I am not aware of the cause of this phenomenon, for it takes place not when we stand with our backs to the sun, but in clouds near the sun itself, irregularly and over indefinite spaces, sometimes taking place in the body of the cloud. The colors are distinct and vivid, but have a kind of metallic lustre upon them.

1.3. An example of succinct but intense

beauty-description

Dylan Thomas, "Poem in October,"

excerpt.

The poet walks out early on his 30th birthday

from his Welsh village by the sea into the country: "I walked abroad in a

shower of all my days".

..........................................

A springful of larks in a rolling

Cloud and the roadside bushes brimming with whistling

Blackbirds and the sun of October

Summery

On the hill's shoulder,

Here were fond climates and sweet singers suddenly

Come in the morning where I wandered and listened

To the rain wringing

Wind blow cold

In the wood faraway under me.

Pale rain over the dwindling harbour

And over the sea wet church the size of a snail

With its horns through mist and the castle

Brown as owls

But all the gardens

Of spring and summer were blooming in the tall tales

Beyond the border and under the lark full cloud

There could I marvel

My birthday

Away...

1.4. An off-beat appreciation of usually

disregarded aesthetic objects

The French painter and sculptor Jean

Dubuffet (b. 1901) writes rapturously of things that traditionally were

despised as highly "unaesthetic."

(From Empreintes, 1957;

excerpted from Herschell Chipp,

Theories of Modern Art, 1968.)

I like to proclaim that my art is an attempt to bring all disparaged values into the limelight. Also, I am more curious about these elements than about all the others, because they are so prevalent as to be always in sight. The voices of dust, the soul of dust, interest me a great deal more than the flower, the tree, or the horse, for I have a feeling that they are more extraordinary. Dust is a being so different from us. Just that absence of defined form ... one might want to change into a tree, but to change into dust-- into such a continuous existence -- would be so much more tempting. What an experience! What information!

Dubuffet admits to 'a fascination with

untouched traces,' and declares himself to be 'in all spheres, smitten with

savagery.'

Would you rather, reader, friend, that I traveled, that I took you to absurd countries, led you before mosques, pagodas, Persian markets, tropical rivers, coral reefs. Kindly think seriously about the inanity of dimension. It is a mad prejudice, a vulgar trap, which makes you marvel at your snowcapped peaks, high cliffs, your gardens of rare species, or your elegant islands. Burn scale! Look at what lies at your feet! A crack in the ground, sparkling gravel, a tuft of grass, some crushed debris, offer equally worthy subjects for your applause and admiration. Better! For what is more important is not reaching objects of reputed beauty after long days of travel, but learning that, without having to move an inch, no matter where you are, all that first seemed most sterile and mute is swarming with facts which can entrance you even more. The world does not extend over one single plane, all on the surface. The world is made in layers, it is a layer cake. Probe its depths, without going any further than where you stand, you will see! I am speaking figuratively, you understand.

The probing, Dubuffet explains, requires a

special intensity:

But take care, this is a venture in which a certain spiritual position in the operator is more necessary than anything else; this is an operation whose success is dependent above all upon a certain forcing of the thoughts, a certain over-excitement which augments conduction, facilitates the transformation of one order of ideas into another, makes all parts of the mind permeable, so that currents can pass without restriction. Therefore, please allow me my grasses and tufts of weeds, allow me my common plants which, by their very commonness, exercise a stimulating effect on my spirit. Heat, a high spritual temperature, is needed in my business.

The veil obscuring the real character of

things falls away only when the observer achieves a self-forgetful state of

naturalness or spontaneity:

Plants or people, or everything existing, each has a mask all ready with which to reply to tiresome inquiries, and it is only by this mask that we usually know them. The truth is that no one wants to be looked at; each one, the instant he senses a stare, and before having been touched by it, pulls the painted curtain. The indiscreet always get caught! Return with their painted curtains thinking that they have something -- having seen nothing, suspected nothing of the real creatures behind them. You must have savoir faire to unveil the creature and have it dance in your presence, forgetting that it is watched. For everyone dances and does nothing but dance; living and dancing are one and the same thing; indeed each thing is finally no more than a specific dance; the dance is the thing. Dancing is the subtle word for living, and it is only by dancing too that one can discover anything. One must approach dancing. He who has not understood that will never know anything about anything. All the faults dance badly -- dance stiffly, too laboriously, watch themselves dance, do not forget that they are dancing. He who dances will not endure a stare, especially his own. Socrates, the point is not to know, but to forget, oneself....

Dubuffet's orientation toward the unbeautified natural phenomenon goes hand in hand with a

curious impression which he himself seems to concede lacks any rational

foundation.

I will permit myself to add, parenthetically, that I am perhaps more sensitive than just anyone to phenomena from which the intervention of the human hand has been totally eliminated, because of a certain temperamental disposition peculiar to me, which leads me to attribute, contrary to popular opinion, less intelligence, less knowledge, less power, to the human being than to other beings of the natural world, and indeed to those which are rather more often considered out of the question in this sphere, such as plants or stones. I can not rid myself of the constant impression that consciousness -- that endowment of which man is so proud -- dilutes, adulterates, impoverishes, as soon as it intervenes; and I feel most confident when it does not seem to be present.

A closely associated idea, of slightly higher

standing in the history of natural philosophy, is that of the animate, indeed

psychic, character of all natural objects -- which Dubuffet is quite ready to

extend to momentary states of things (a wave, a shadow, a gesture)!

No one contests the breath of life is found in minerals as well as plants or animals, and whoever hesitates at that has only to think of the polyhedric crystal, which aspires with all its will to form, and finally does form, the rock. At this point, we are quite easily led to expand our idea of what is embraced by the term being -- although not without a slight hesitation -- to certain elements, no longer isolated and with well-defined contours, like the leaf of a tree or the crystal, but continuous and having neither form nor limited quality, such as coal, metal, water. But what of the momentary and moving, of the wave which forms for an instant in the great open sea; is it a being? If a will -- no matter how obscure, how vacillating -- appears in any part of the inert mass, even for a very short time, does this not suffice to make a being? Is the shadow of a walker a being like the walker himself? And the step of the walker, his walk, are they beings? Where does one begin, where does one end, in the use of the term being?

Comment

Whatever we think of Dubuffet's beliefs about

natural objects we can hardly deny that Dubuffet's experience, as described, is

aesthetic. Whether such experience has any chance of yielding knowledge of the

sort Dubuffet thinks it gives, is another matter altogether. We may also wonder

whether his delight partly depends on his belief. Perhaps dust and pebbles

would not look as beautiful to him were it not for his belief in their being

animate.

1.5. Sarah Hubbell

on the beauty of insects. From Broadsides

from the other orders: a book of bugs, 1993, pp. 138-9.

Although some people who are not familiar with them think of bugs as ugly, you can't be around entomologists for long before bug handsomeness becomes obvious. When I talked to Cassie Gibbs about black flies I asked her how it was she had specialized in mayflies, which appear to have wings made of isinglass. "They are such beautiful insects," she said forthrightly. But it was Asher [Treat] who first introduced me to bug beauties beyond normal human seeing. One day he invited me to inspect a tiny moth, undistinguished and dun-colored to the naked eye. Under the microscope it revealed itself, shimmering, gleaming, golden, decked out in mothly splendor. A goldsmith would have been impressed by its exquisiteness, and so was I. The scanning electron microscope opened up a new world of information and study for entomologists, just as it did for scienctists in other fields, but it also opened up a new world of beauty. I have a copy of A Scanning Electron Microscope Atlas of the Honey Bee,nearly 300 pages of SEM photos of bees, photos of surpassing loveliness of shape, texture, and form. I know a sculptor who uses it to give him inspiration for his work.

1.6. The Japanese Wabi-sabi

aesthetic

1. An excerpt from Wikipedia "Wabisabi"

Wabi now connotes rustic simplicity, freshness or quietness, and can be applied to both natural and human-made objects, or understated elegance. It can also refer to quirks and anomalies arising from the process of construction, which add uniqueness and elegance to the object. Sabi is beauty or serenity that comes with age, when the life of the object and its impermanence are evidenced in its patina and wear, or in any visible repairs.

From an engineering or design point of view, "wabi" may be interpreted as the imperfect quality of any object, due to inevitable limitations in design and construction/manufacture especially with respect to unpredictable or changing usage conditions; then "sabi" could be interpreted as the aspect of imperfect reliability, or limited mortality of any object, hence the etymological connection with the Japanese word sabi , to rust.

A good example of this embodiment may be seen in certain styles of Japanese pottery. In the Japanese tea ceremony , the pottery items used are often rustic and simple-looking, e.g. Hagi ware , with shapes that are not quite symmetrical, and colors or textures that appear to emphasize an unrefined or simple style. In reality, these items can be quite expensive and in fact, it is up to the knowledge and observational ability of the participant to notice and discern the hidden signs of a truly excellent design or glaze (akin to the appearance of a diamond in the rough). This may be interpreted as a kind of wabi-sabi aesthetic, further confirmed by the way the colour of glazed items is known to change over time as hot water is repeatedly poured into them ( sabi ) and the fact that tea bowls are often deliberately chipped or nicked at the bottom ( wabi ), which serves as a kind of signature of the Hagi-yaki style.

2. JB's commentary on Yuriko Saito's explanation of Wabi-Sabi

The Japanese aesthetic of imperfection and insufficiency is quite puzzling. Naturally one turns to explanations by specialists. One such is found in an article by Yuriko Saito, “The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55, 4 (Fall 1997) 377-385. Her purpose is to show that ugliness or imperfection can indeed be aesthetically prized. Her account has the virtue of recognizing the complexity of the factors that go into the Wabi-Sabi view of things. But problems arise in taking it as a coherent celebration of ugliness or imperfection.

(1) Some of the values cited by Saito seem not to concern the ugly but only mixed cases of mild unbeauty offset by aspects of subdued beauty. Such are worn surfaces, which may have a pleasing patina or weathered surfaces in which the grain gains saliency. We need more enlightenment as to what exactly is deemed beautiful about the worn plate and the cracked tea cup, and what would count as an exceptionally good Wabi-Sabi example. (2) At some places Saito's account suggests that the judgment exercised in the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic is skewed: it “overcompensates” for naïve and courtly love of luxury and ostentation. This appears to imply that it is invalid, that those who relish the worn surfaces overvalue them.. (3) In some cases non-aesthetic considerations seem mixed with aesthetic ones. Political expediency is said to influence the endorsement of the values; endorsing the aesthetic becomes a self-protective “gesture toward social egalitarianism” on the part of nervous nobles. (381) At another point she characterizes the aesthetic as a movement among cultural elite nostalgic for lost status and wealth. This amounts to a cryptic form of sour grapes. (4) A philosophical or spiritual version of the aesthetic is ascribed to Zen Buddhists who seek the Buddha nature “which makes no discriminations between various objects and activities.” (381f) Taken literally this won't wash as an aesthetic point of view since that necessarily distinguishes between better and worse. Rather it amounts to a principled suppression of the aesthetic point of view in favor of a spiritual one.

These and a number of other elements in Saito's account give grounds for doubting the whole qualifies as a straightforwardly aesthetic elevation of the unbeautiful over the beautiful. Its purer forms seem rather to be refined sorts of aesthetic self-denial for the sake of spiritual beauty in oneself. Perhaps the prudent ruler if candid would claim that the element of hypocrisy in his celebration of the unbeautiful is aimed at producing a beautifully even-tempered civil society. In neither case is the orientation, as described, consistently and sincerely aesthetic.

In class I will give a powerpoint segment on this aesthetic taken as such.

1.7. A consoling beauty in a mass of

aged flesh. Edith Wharton, Age of Innocence, Bk. 1, Ch. 6, describing Mrs. Manson Mingott.

The immense accretion of flesh which had descended on her in middle life like a flood of lava on a doomed city had changed her from a plump active little woman with a neatly-turned foot and ankle into something as vast and august as a natural phenomenon. She had accepted this submergence as philosophically as all her other trials, and now, in extreme old age, was rewarded by presenting to her mirror an almost unwrinkled expanse of firm pink and white flesh, in the center of which the traces of a small face survived as if awaiting excavation. A flight of smooth double chins led down to the dizzy depths of a still-snowy bosom veiled in snowy muslins that were held in place by a miniature portrait of the late Mr. Mingott; and around and below, wave after wave of black silk surged away over the edges of a capacious armchair, with two tiny white hands poised like gulls on the surface of the billows.

Needless to say the almost wrinkled expanse

of pink and white flesh that Mrs. Mingott presents to

her mirror consists only of her face and as much of her upper chest as is

decent to expose to her view. Still, such small consolations

help make human life bearable.

1.8. A truly beautiful state of mind

One of the all-time great foot-travelers and

travel writers, Patrick Leigh Fermor, who was also a

World War II hero and the master of many languages, provides a sterling example

of a beautiful state of mind in his book, A Time to Keep Silence. He

recounts his experience in 1953 in the Abbey of Saint-Wandrille

in Normandy, to which he had repaired as a visitor in order to have absolute

tranquility to write his first book. The extreme isolation imposed by the

monastic discipline – no talking to almost anyone, no contact with the outer

world, only simple food and water to drink, etc. initially brought on a state

of depression. He couldn't write. He suffered from insomnia; then a period when

he slept as if drugged, waking only for meals. He continues:

Then began an extraordinary transformation: this extreme lassitude dwindled to nothing; night shrank to five hours of light, dreamless and perfect sleep, followed by awakenings full of energy and limpid freshness. The explanation is simple enough: the desire for talk, movement and nervous expression that I had transported from Paris found, in this silent place, no response or foil, evoked no single echo; after miserably gesticulating for a while in a vacuum, it languished and finally died for lack of any stimulus or nourishment. Then the tremendous accumulation of tiredness, which must be the common property of all our contemporaries, broke loose and swamped everything. No demands, once I had emerged from that flood of sleep, were made upon my nervous energy: there were no automatic drains, such as conversation at meals, small talk, catching trains, or the hundred anxious trivialities that poison everyday life. Even the major causes of guilt and anxiety had slid away into some distant cave and not only failed to emerge in the small hours as tormentors but appeared to have lost their dragonish validity. This new dispensation left nineteen hours a day of absolute and god-like freedom. Work became easier every moment; and, when I was not working, I was either exploring the Abbey and the neighboring countryside, or reading. The Abbey became the reverse of a tomb – not, indeed, a Thelema [a potion leading to a sense of release from all inhibitions] or a Nepenthe [a potion that induces forgetfulness], but a silent university, a country house, a castle hanging in mid-air beyond the reach of ordinary troubles and vexations…

That's as close to heaven as I think we need

to get! Fermor elsewhere calls it "a state of

peace that is unthought of in the ordinary

world." This is what I meant when I said that the state of mind implied by

Kirwan's thirst for a beauty beyond beauty would not

bear comparison with a life blessed with finite but exalted states of being.

Interestingly the ethereal state enjoyed in

his best days in the Abbey gave way to acute distress immediately he returned

to the outside world: "the outer world seemed afterwards, by contrast, an

inferno of noise and vulgarity entirely populated by bounders and sluts and

crooks...From the train that took me back to Paris, even the advertisements for

Byrrh and Cinzano seen from

the window, usually such jubilant emblems of freedom and escape, had acquired

the impact of personal insults."

2. The Neoplatonic

impulse to ascend to Beauty Itself as inherent to aesthetic experience and Kirwan's phenomenological version of this.

Plotinus takes over Plato's notion of the

great chain of beauty, as it might be called, the ranking of realities from the

least to the greatest in beauty, culminating in Beauty Itself. As has already

been pointed out, there are terrific difficulties in working out the details of

such a picture. It's hard enough to imagine ranking everything in relation to

everything else even within particular domains, the animal kingdom, for

instance, let alone nature as a whole, let alone nature as opposed to culture,

etc. But it seems clear that Plato and Plotinus were not all that interested in

the details. Their eye was mainly fixed on the transcendent, off-the-scale

destination – as well as on a few big steps, such as from individuals to

properties, from physical beauties to intellectual beauties. With this

orientation, the lofty end-state of contemplating Beauty Itself (in Plotinus

the "One") trumps any experience, however impressive, of the myriad

details like the ones we have been sampling. And Plotinus makes the process of

rising up to that level sound quite wonderful, doesn't he? If only we believed

in ourselves, in our capacity to prune away the squalor and triviality in our

souls, his account of lifting ourselves up to grasp the unspeakable brilliance

of Pure Beauty would be enthralling, wouldn't it? Like the religious mystic's

account of seeing, or dwelling within the presence of, the unspeakable majesty

of God.

Actually, the accounts of experiencing the

primal realities (God, Beauty Itself) are conspicuously spare, uninformative.

Most of the descriptive content concerns the object, the remainder being how wonderful,

blissful, rewarding, breath-taking the experience is. There's nothing specific

about what that experience is like, nothing sensory or conceptual. A common

theme in all the accounts is the ineffability of the experience, which means

the impossibility of putting it into words. In this respect the mystical

experiences are quite unique. Other things called inexpressible are not really

inexpressible: love, sexual ecstasy, beauty-rapture, drug highs, and their

negative counterparts, and so forth. They just take analytic effort, sustained

noticing of features, and then semantic invention to find descriptions that

fit.

Informative or not, the Neoplatonists'

accounts are apt to seem somehow right, at least in pointing toward an ideal.

They have seemed so to countless people over the ages, so we should try to

understand their appeal. Let's see what momentum the great chain of beauty

generates and how that might lead us on to the apex. The key attribute of the

top level is that it is abstract. So if we can understand the appeal of the

abstract we will make progress. Since the process of abstraction begins at the

second level of the chain, let's concentrate on that. As we move from the

beauty of particulars to the beauty of properties, what happens? The object of the experience changes. It was a particular

face (or a particular sounding of a chord, or a particular rose). Then it is a

face-plan, a schema, a type, an arrangement of features, something abstract in

that many particulars can share it. What is involved in experiencing the beauty

of this abstract thing? It's not all that easy to say. One thing we can say it

must involve is finding each fully compliant instance beautiful, that is, each

face that complies with the face-plan. Like admiring slim legs or a slender but

curvaceous silhouette wherever it appears. Strictly this is admiring a

class of instances as opposed to a single one. To admire a class is to

admire each and every member of that class as it comes into view in the flesh

or in memory. But what is it like to admire the very idea of

that sort of face or figure? This is like relishing the thought of that

face-plan without reference to any full-fledged particulars. It's abstract in

that the mental envisagement of the plan lacks the sensory clarity and detail

of any particular face. It's an idea, not a concrete image. Platonists say that

it is purer because of its abstractness. What can this mean? Do your ideas seem

purer than your visual, that is, your perceptual images? In a way they do.

One's ideas come without any of the complications of a perceptual image. That

is, the perceptual image is of things that look different when you come up

close, whereas your ideas finesse all of that. They don't contain the

possibility of closer inspection. So it's as if all the close-up grotesqueness

is purged away, the sticky ridges on the lips, the pores and hairs and jelly in

the corners of the eyes just don't exist in the idea. The skin and everything

else seems immaculate just because all those things are lost in the

abstraction.

(Yet if the face-plan is going to be highly,

richly beautiful it's going to have to be highly specific, not just a schema

for placing the main features. All the contours must be included, so the idea

is a quite complicated one. It won't be easy to think the thought of all those

being just so. This is why designers have to depend so heavily on drawings,

that is, on their visual perception, in order to create a beautiful face-plan.

A consequence of this is that it's not easy to conjure up a really beautiful

abstraction of something as complex as a human face. More on

this in a moment in connection with Cicero's statement about the artist's

idea.)

Another way in which abstractions seem purer

is when they concern only a few features, as when the law of gravity applies to

everything that has mass but only specifies it in respect of its weight and

what follows from that, given its other characteristics. So the law seems purer

than the phenomena it governs. Does this kind of comparative purity, which

boils down to simplicity, make the law more beautiful than its instances?

This is not an easy question, since the

phenomena are much more complex but perhaps have more beauty-dimensions than

the law has. The answer seemed obvious to Plato, but then he had a strong bias

in favor of the abstract. If we give the perceptible world its due, it isn't at

all clear that the enormous variety and vivacity of sensory beauties fails to

match, in overall beauty, the sparer beauties of things abstract, such as

mathematical and physical laws. And if the phenomena turn out to be as

beautiful as the laws, then we are left not with an ascent toward Beauty Itself

but to a much more level field of beauty. There would still be rankings within

categories, but not a "segmented" ranking in which physical things

occupy the lower and abstract things the upper rank. And if that's right then

the drive toward the unattainable loftiness of Beauty Itself seems to rest on a

misunderstanding.

Kirwan (see Beauty-Additions #3) might reply to these

criticisms in either of two ways: (1) He might say that the impulse toward

better and better beauty isn't denied by what was just said. The answer,

however, is that this impulse may be as well satisfied by ascending to higher

beauty within each category: more beautiful music, gardens, theories, and so

forth. There can still be plenty of impossible dreams of super-beauties of all

these kinds, as well as of superabundant cumulative beauty. Beauty Itself need

not be involved at all.

(2) Or he might say that the allure of the

abstract persists, whatever may be said about the equal beauty of particulars.

People want to get away from particulars. They want to lose the sense of time,

to come to a state of fulfillment so encompassing that neither future nor past

matters. That state of timelessness can only be accomplished by focusing on

something as abstract as hyperkalon, Beauty

Itself. Since this is the completest fulfillment we can imagine, it must also

be the most beautiful. (Mystical religions have called it Nirvana.) And, he

might conclude, our thirst for beauty contains the seed of it from the start, a

yearning for a beauty "that no object could satisfy." Such may be his

final defense of our "unappeasable yearning" for beauty.

3. Kirwan, Beauty,

Ch. 3, "Beauty/God," leading ideas summarized and pp. 36-38

excerpted.

In the first chapter, when he is setting

forth his basic theoretical beliefs, Kirwan cites Neoplatonism as the most suggestive of the theories of

beauty as to the inner nature of our experience of beauty precisely because it

stresses how mysterious ("impenetrable") Beauty Itself seems, how

utterly beyond analysis. This mystical tradition, which runs through Plotinus

and Christian mystics inspired by him, treats Beauty Itself as a mystical

reality which is a "beauty beyond beauty," not just kalon but hyperkalon.

Kirwan's distinctive angle on this is to translate

the metaphysical descriptions into descriptions of the experience of beauty --

that is, he gives a phenomenological spin to the older, metaphysical doctrine.

He disavows any literally metaphysical intentions, aiming only at explaining

how such ideas spring naturally from the "structure" of our

experience. (He also repeatedly insists that "beauty" applies only to

experience, not to a property of anything -- thus our beauty-experience is not

literally the experience of beauty. I will ignore this since it is not

strictly necessary to the present point. But it's worth saying in passing that

I think it is a confusion of categories that stifles practical aesthetics. The

historical Neo-platonists at least stood clear of

this muddle.)

In Plotinus, as we have already seen from the

selections in the core text, Beauty Itself comes across as more than a property,

as some kind of active being – in that respect being like a god with the power

to create, only as abstract a god as could be, with nothing at all in the way

of personality (no anger or love or expectations). More like a radiant force,

like light, but having nothing physical about it. Beauty so conceived (if such

mystical thinking can be called conceiving) is understood in terms of a special

class of analogies. The analogies used are understood not to be literally descriptive. Thinking with them was not analogical in the ordinary

sense precisely because they couldn't be fully grasped (by

our "finite" intelligences). When the theologians of the Christian

era spoke of God as being Beauty itself they told us to think of his beauty as

transcending ordinary beauties infinitely in the

direction of superiority. By such superlatives they counseled us to give up all

hope of forming a coherent concept of it and accept its utter and absolute

incomprehensibility.

To be sure hope is held out that after death

the blessed in Paradise will be less baffled, more enlightened, will understand

better. But the sort of intellect this blessedness implies is as

incomprehensible as the object of its adoration.

Aside from the metaphysics the ancient texts

contain descriptions of the experience the Neoplatonic

devotee has, which involves the following elements.

1.

a sense of

earthly beauty being a distant sign of the divine perfection.

2.

a sense of

Beauty Itself being incomparably more beautiful than sensible beauty of any

sort. Nothing sensible can be beautiful in all of its properties. There is

bound to be unbeauty in it. Beauty Itself is purely

beautiful.

3.

a sense of

Beauty itself being far more beautiful than any invisible beauty that we can

conceive of, as in mathematics or other abstract domains of knowledge.

4.

an emotional

tone of distress or melancholy at the vast distance between the beauties we can

conceive of and Beauty itself.

5.

a yearning to transcend the limitations of our natures

Kirwan's argument is that something like the Neo-platonic

experience of beauty is latent even in our ordinary experience of beauty. If we

probe it deeply enough we will find within our delight in the beauty of a

person or flower or theorem, lying at a deep level, a sense of an unattainable,

ungraspable beauty which the beautiful particular only dimly reflects. Here is

how he puts it.

Part of the phenomenality/psychology of beauty...is that it is always incomplete. This incompleteness is something reflected in what might be called the ‘Ideal' theory of Neoplatonism, is, indeed, perhaps its very origin. It is expressed by Plotinus in the idea that matter can never be wholly mastered by the pattern which is the Idea – for it would then be that Idea – and so can never be wholly beautiful, and in what Ficino [a 15th century Florentine Neo-platonist] calls the rule of Necessity, that phenomenal beauty exists in matter, place, time, and form, and is thus less perfect than that beauty which is bound by none of these...It is the feeling that...beauty is as much a token as a presence, which expresses itself in the ascription of timelessness to moments of beauty.

But beauty is also time in the midst of timelessness. The notion of the hyperkalon, for the sake of which Plotinus even asserts we should forego beauty, begins with the phenomenon/act itself...The notion of a beauty beyond time or Necessity, of beauty as, paradoxically, in being phenomenal, in itself incomplete in itself, is part of the perception of beauty. That is, we experience beauty not as a consummation but as an intimation. Hence it is that to describe this perception as simply a form of pleasure or delight seems absurdly reductive, for it is experienced as both a transcendence and a falling short... This is the peculiar nature of beauty which has led its [Neoplatonic] theorists, ...to assert that our pleasure is not simply one pleasure among others...[but rather is] a yearning for the ultimate beatitude. What I wish to assert now, abandoning any commitment to the transcendental in a theological sense, is that beauty is a yearning without object...[Such] Yearning differs from simple desire in that it posits a degree of desirability in the object that it would seem that no object could ever satisfy. It differs from simple dejection insofar as this impossibility of being satisfied does not lead it to relinquish its fundamental orientation towards the object – it is an ecstasy of despair. For these reasons yearning seems the best characterization of the kind of pleasure we feel in beauty; a pleasure, pervasive and intense, that is a combination of delight, regret, desire, and resignation.

Kirwan connects this unappeasable yearning with the

metaphysical longing for ultimate explanations that philosophers have tried to

provide, always with less than full success.

Reviews or discussions of James Kirwan: Jennifer

A. McMahon, web (Google, Kirwan - Beauty/p.1

Jenny's Home Page; Crispin Sartwell, web (Google,

Kirwan – Beauty/p.1 by Crispin Sartwell

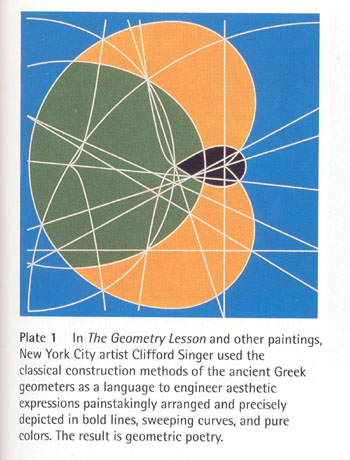

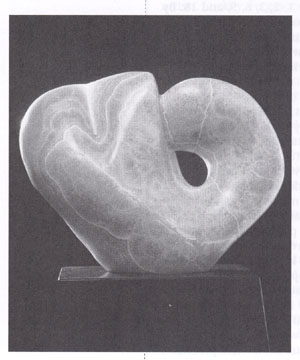

4. Mathematical beauty exhibited in recent

art. These examples are taken from Ivar Peterson, Fragments

of Infinity: a kaleidoscope of mathematics and art, John Wiley and Sons,

Inc., 2001.

Here are several of the many fascinating

images in this book, which is recommended to anyone interested in the

intersection of presentday art and mathematics. The

captions are either verbatim quotations from the book or statements built out

of quotations.

1 2.

2.

2. Helamen

Ferguson, Eine Kleine

Rock Musik III. To create Eine

Kleine Rock Musik III,

Ferguson quarried a sixty-pound piece of creamily streaked honey onyx in Utah, then carved it into a topological shape of a Klein bottle. A

Klein bottle has a curiously contorted surface that passes through itself and

emerges again from the other side.

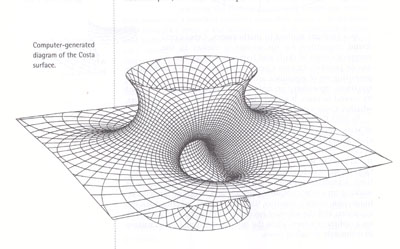

3. Celso Costa

originally discovered this kind of surface by devising equations inspired by

the sweeping curves of skirts and hats worn by dancers in Rio de Janeiro's

famous Carnival. These equations represented an unbounded minimal surface

threaded by several tunnels. Other researchers discovered by use of computer

images based on the equations that the surface did not intersect itself. Hence

it was a member of an elite group, the other members being the plane, the catenoid and the helicoid.

The figure (above) has the splendid elegance

of a gracefully spinning dancer flinging out her full skirt so it whirled

parallel to the ground. A gentle wave ruffled the skirt's hem. Two holes

pierced the skirt's lower surface and joined to form a tunnel that swept

upward. Another pair of holes, set at right angles to the first pair, led from

the top of the skirt downward into a second tunnel.

The Costa surface is one of an infinite

number of such unbounded minimal surfaces, each with a different number of

tunnels penetrating the form's interior and opening up into wide mouths, like

trumpet bells. (162-3)

[JB's comment: Although the Costa surface

image is an purely mathematical diagram, it invites

artists to make use of it. In that way it belongs in this section. In class I

will exhibit materials from a website of a mathematician, Thomas Banchoff. The address is:

http://www.geom.uiuc.edu/~banchoff.]

5. THE BEST OF PHYSICS: What Makes an

Equation Beautiful?

By KENNETH CHANG

CONSIDER a verbal description of the effect

of gravity: drop a ball, and it will fall.

That is a true enough fact, but fuzzy in the

way that frustrates scientists. How fast does the ball fall? Does it fall at

constant rate, or accelerate? Would a heavier ball fall faster? More words,

more sentences could provide details, swelling into an unwieldy yet still

incomplete paragraph.

The wonder of mathematics is that it captures precisely in a few symbols what

can only be described clumsily with many words. Those symbols, strung together

in meaningful order, make equations - which in turn constitute the world's most

concise and reliable body of knowledge. And so it is that physics offers a very

simple equation for calculating the speed of a falling ball.

Readers of Physics World magazine recently were asked an interesting

question: Which equations are the greatest?

Dr. Robert P. Crease, a professor of philosophy at the State University of New

York at Stony Brook and a historian at Brookhaven National Laboratory, posed

the question in his Critical Point column and received 120 responses,

nominating 50 different equations. Some were nominated for the sheer beauty of

their simplicity, some for the breadth of knowledge they capture, others for

historical importance. In general, Dr. Crease said, a great equation

"reshapes perception of the universe."

The mathematical equation providing the speed of a falling ball is just four

symbols long: v = gt.

With it, you can calculate the ball's speed 2.5

seconds after release. (That's g, the acceleration of gravity, which is 32 feet

per second squared, multiplied by 2.5 seconds, giving an answer of 80 feet per

second.)

This equation, a mainstay of high school physics, was not among those nominated

as the greatest of all time, which is not surprising, because its use is

limited.

The pull of gravity varies with distance from the Earth's surface, and the

equation also suggests that an object's speed could go on increasing toward

infinity, past the known limit of the speed of light.

The top vote-getters in the magazine poll were Maxwell's equations - a set of

four that describe the interplay between electric and magnetic fields - and

Euler's equation, a purely mathematical construct that finds wide use in

theoretical physics.

"It combines rational and irrational numbers to get zero," Dr. Crease

said. "It's bizarre."

Among the other nominees were the all-familiar E=mc2 from Einstein, which

equates energy and matter; the Pythagorean theorem;

and Isaac Newton's F=ma.

Prominent scientists have their own favorites. Dr. Brian Greene, a theorist at

Columbia University and author of "The Elegant Universe," cites

Einstein's general relativity equations, which describe how matter warps the

fabric of space, and the Schrödinger equation, the fundamental equation of

quantum mechanics.

"With a mere handful of symbols, those equations describe almost all

phenomena in the universe," he said. "It is so amazing how so much of

the universe is encapsulated in a few symbols."

Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden

Planetarium, said he was disappointed that E=mc2 did not receive more votes.

"I think the general physics community, they're a little bored with the

equation," he said. "It's risen to the level of icon that people no

longer pay attention to."

But Dr. Tyson said that the equation was a fundamental underpinning not only of

the universe, but also of the first five chapters of his book

"Origins."

"It's simple, yet profound," he said. "I'd be less impressed if

it were a big complicated equation."

A half-dozen of Dr. Crease's respondents, including Richard Harrison of

Calgary, Alberta, chose one of the simplest possible equations.

Mr. Harrison wrote: " '1 + 1 = 2' is the fairy

tale of mathematics, the first equation I taught my son, the first expression

of the miraculous power of the mind to change the real world. I remember my son

holding up the index finger, the 'one finger,' of each hand as he learned the

expression, and the moment of wonder, perhaps his first of true philosophical

wonder, when he saw that the two fingers, separated by his whole body, could be

joined in a single concept in his mind."

Copyright 2004 The

New York Times Company

6. Jonathan Swift on the Laputans' obsession with mathematically regular forms, from

Gulliver's Travels, 1729.

Here we have a description of the imaginary Laputan culture, in which things like Marquardt's

beauty-mask might be highly prized -- one that is not put off by the conflict

between natural and geometrical forms that I complained of in class. Music is

associated with mathematics because of the mathematical ratios exemplified by

the harmonies within the overtone scale. (The shape of musical instruments,

however, is only loosely associated with those properties.)

[The Laputans'] Ideas are perpetually conversant in Lines and Figures. If they would, for Example, praise the Beauty of a Woman, or any other Animal, they describe it by Rhombs, Circles, Parallelograms, Ellipses, and other Geometrical Terms, or else by Words or Art drawn from Musick, needless here to repeat...

They also apply geometry to the carving of meat and other dishes that lent themselves to being shaped: "In the first Course, there was a Shoulder of Mutton, cut into an AEquilateral Triangle; a Piece of Beef into a Rhomboides; and a Pudding into a Cycloid. The second Course was two Ducks, trussed up into the Form of Fiddles; Sausages and Puddings resembling Flutes and Hautboys, and a Breast of Veal in the Shape of a Harp. (1) The Servants cut our Bread into Cones, Cylinders, Parallelograms, and several other Mathematical Figures."

[1. This symbolism is only

loosely or indirectly associated with the mathematics, of course.]

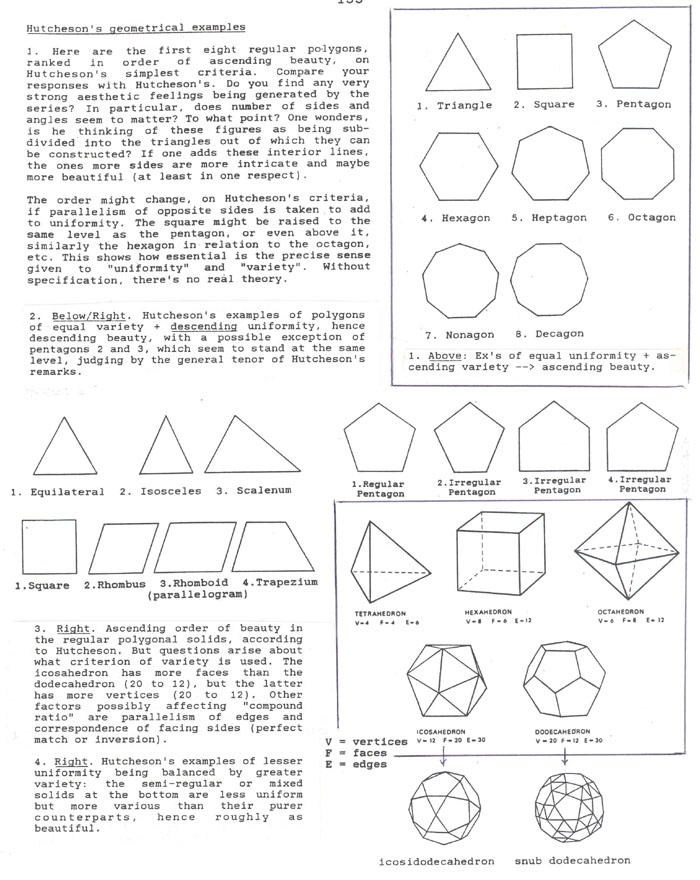

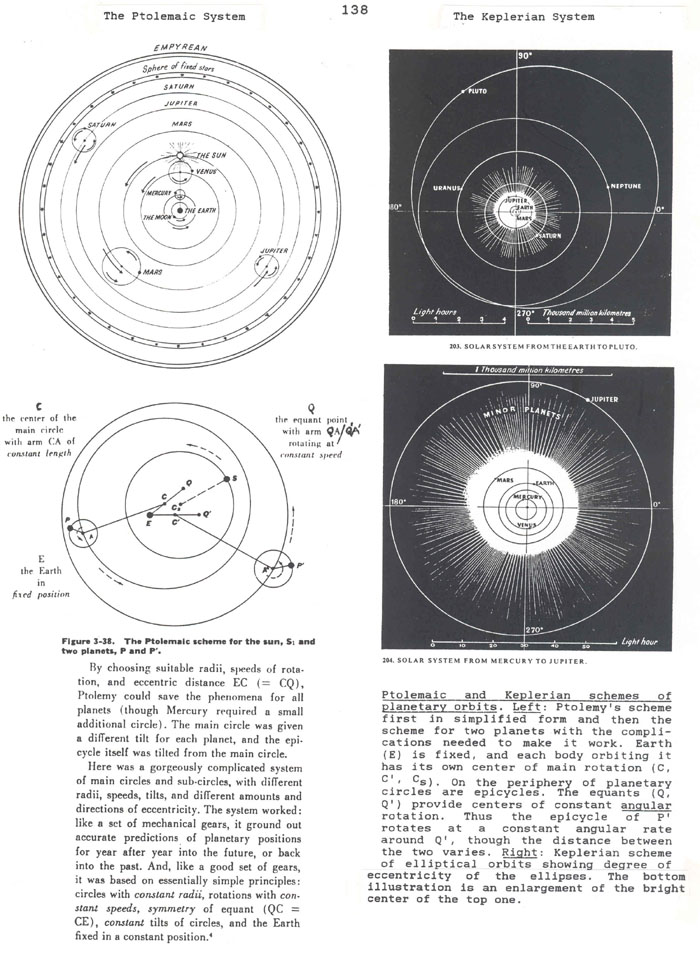

7. Hutcheson's application of the

criterion of uniformity and variety to geometrical and astronomical examples.

8. Modes of architecture (in reference to

Apollonian v. Dionysian beauty)

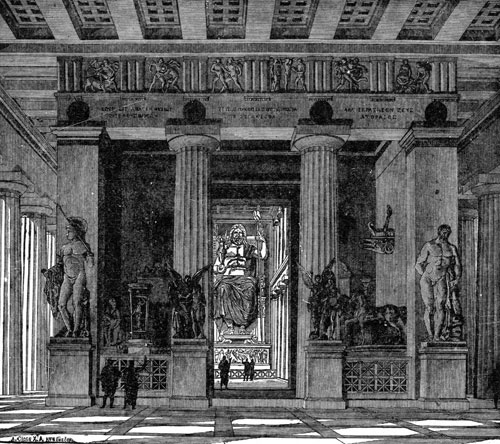

8.1 Classical Greek temple design

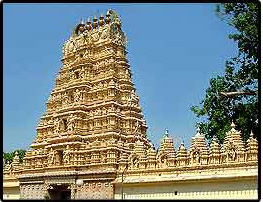

8.2. Two arguably Dionysian modes, Gothic

cathedrals and Hindu temples

8.3. An intermediate case, cool modernism,

National Gallery East Wing

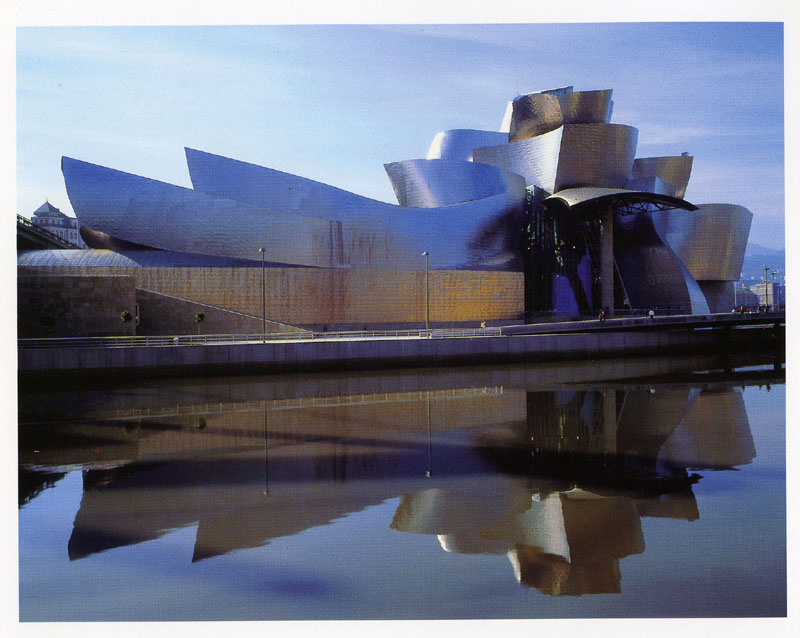

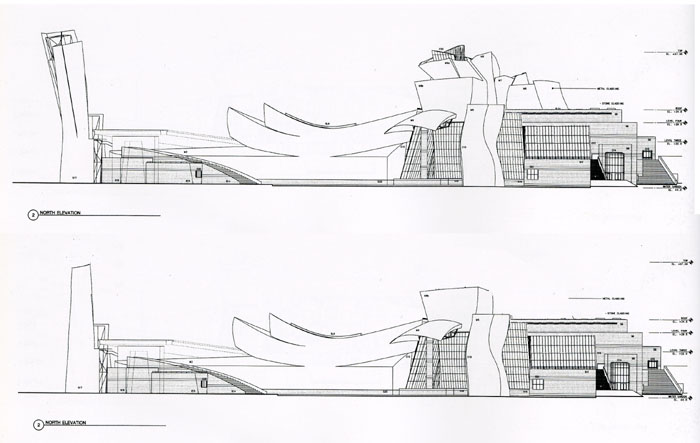

8.4. Frank Gehry's complexly flowing architecture. And where do these works fit on the

Apollonian-Dionysian scale? How are its beauties to be described?

Here are, in order, a conceptual sketch, a

north and a west elevations, and the finished building

seen from the north. The building is discussed briefly in Item 8 in the

Discussions folder. Descriptions given after the pictures are culled from Kurt

W. Forster, Frank O. Gehry: Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, 1998. The photograph here and those shown in class

are from the same volume, and are by Ralph Richter.

Forster's description of

the building (excerpts). "...the museum has been anchored in the cityscape

of Bilbao [Portugal] like a vast circus tent surrounded by a congerie[s] of caravans, for the variety of events

anticipated to take place there requires large and ever varying venues.

Subsidiary spaces are clustered together, squeezed through the bottleneck

between river and embankment, made to duck under bridges, and finally allowed

to soar over the building's core in a spectacular canopy. All this implies

motion induced by internal tension and external compression and gives rise to

the towering and seemingly revolving space of the central hall.." And later, "...the Bilbao Guggenheim must be

reckoned overweight, overdone, and overwhelming. Its excessive qualities are

precisely those that enable it to assume several different roles at once. It is

an immovable pile in the city and a sinuous creature draping its body along a

narrow ledge above the river. As a luminous cave on the inside, and a metallic

mountain from without, the museum appears to be both a perfect fit and a

perfect stranger in its site. Excess designates the state of the building,

exuberance its true nature." And, "From the very start, the sketches

for Bilbao seemed to have the capacity to soar. They expanded energy as if it were free, and this freedom not only generated forms

previously thought to be impossible, but also unfit for integration into a

complicated site." Forster also emphasizes how Gehry

thinks of the complexly curvilinear elements of his buildings as bodies which

he "sets...in motion as a choreographer does his or her dancers."

Following-up the class discussion of the

order in Gehry's design, here are two simplifications

of Gehry's design, intended to test whether people

prefer a comparatively simpler order in a building of this type. Of course I

concede that my simplification may produce aesthetic disharmony, since I have

altered things using only the forms I could copy and paste in Photoshop. There

is also the unknown impact on the interior space, but let us suppose that is

essentially like the effect on the exterior. Compare the modified designs with

the original shown above. Also ask yourself whether Forster's description

applies equally to these simplifications.

9. Illustrations for lecture on

Apollonian and Dionysian beauties.

a. Arguably Dionysian pottery and

sculpture: Pre-Columbian pots and a contemporary Venus-Gaia sculpture.

Mayan vessel

Peruvian vessel (Mocha culture)

Marko Fields sculpture

b. Apollonian color preferences:

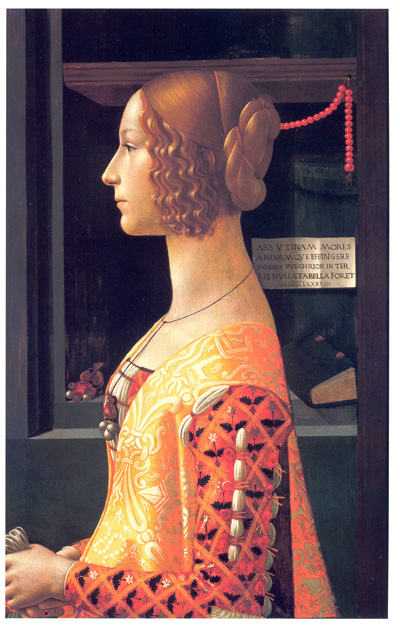

Clear, well-differentiated color as in Ghirlandaio's portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni.

An example of Dionysian color

preference: Domienico Feti,

Flight into Egypt,

1621-23.

Radically Dionysian painting: Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 1911:

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/show-full/piece/?search=Improvisation%2028%20(second%20version)&page=&f=Title&object=37.239

See also Van Gogh's Starry

Night and Alberto Giacometti's Portrait of a

Man in Beauty Notes 24, "Apollonian and Dionysian."

Incontestably

Dionysian music.

Led Zepplin, "Whole Lotta

Love" http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PU-PoUwECjI

Possibly a fusion

of Apollonian and Dionysian music. Beethoven.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kcOpyM9cBg&feature=fvw

10. A fictional aesthete of scent and

flavor (radically Dionysian)

Karl Joris Huysmans

(1848-1907) published his novel A Rebours (Against

Nature or Against the Grain )

in 1884. It created a sensation in Paris, instantly becoming a beacon for

the "decadents" in European culture of the end of the century. Its

protagonist, Des Esseintes, is an eccentric

aristocrat, the last of his line, whose neuraesthenia

(hyper-sensitivity) is almost heroic. The following excerpts are from Chs. 4 and 10. In some ways, and up to a point, he is an

energetic aesthetic investigator and insightful literary critic. But ultimately

his Dionysian excess does him in. His overexcited senses become really

deranged.

Des Esseintes stood gazing at the turtle where it lay huddied together in one corner of the dining-room, flashing fire in the dim half light.

He felt perfectly happy; his eyes were intoxicated with the splendours of these flowers flashing in jewelled flames against a golden background. Then, contrary to his use, he had an appetite and was dipping his slices of toast spread with superexcellent butter in a cup of tea, an impeccable blend of Si-a-Fayoun, Mo-you-tann and Khansky,-yellow teas, imported from China into Russia by special caravans.

This liquid perfume he drank from those cups of Oriental porcelain known as egg-shell china, so delicate and transparent are they; in the same way, just as he would have nothing to say to any other save this adorably dainty ware, he refused to use as dishes and plates anything else but articles of genuine antique silver-gilt, a trifle worn so that the underlying silver shows a little here and there under the film of gold, giving a tender, old-world look as of something fading away in a quiet death of exhaustion.

After swallowing his last mouthful, he went back to his study, whither he directed a servant to bring the turtle, which obstinately declined to make the smallest effort towards locomotion.

Outside the snow was falling. In the lamplight, ice arabesques glittered on the dark windows and the hoar-frost sparkled like crystals of sugar on the bottle-glass panes speckled with gold.

A deep silence wrapped the little house that lay asleep in the darkness.

Des Esseintes stood lost in dreams; the logs burning on the hearth filled the room with hot, stifling vapours, and presently he threw the window partly open.

Like an overhanging canopy of reversed ermine, the sky rose before him, a black curtain dappled with white.

An icy wind was blowing, that sent the snow spinning before it and soon reversed this first arrangement of black and white. The sky returned to the correct heraldic blazon, became a true ermine, white dappled with sable, where the black of night showed here and there through the gcneral whiteness of the snowy mantle of descending snowflakes.

He closed the window again. But this quick change, without any intermediate transition, from the torrid heat of the room to the cold of mid-winter had given him a shock; he crouched back beside the fire and thought he would swallow a dose of spirits to restore his bodily temperature.

He made his way to the dining-room, where in a recess in one of the walls, a cupboard was contrived, containing a row of little barrels, ranged side by side, resting on miniature stocks of sandalwood and each pierced with a silver spigot in the lower part.

This collection of liquor casks he called his mouth organ.

A small rod was so arranged as to connect all the spigots together and enable them all to be turned by one and the same movement, the result being that, once the apparatus was installed, it was only needful to touch a knob concealed in the panelling to open all the little conduits simultaneously and so fill with liquor the tiny cups hanging below each tap.

The organ was then open. The stops, labelled "flute," "horn," "vox humans," were pulled out, ready for use. Des Esseintes would, imbibe a drop here, another there, another elsewhere, thus playing symphonies on his internal economy, producing on his palate a series of sensations analogous to those wherewith music gratifies the ear.

Indeed, each several liquor correspondcd, so he held, in taste with the sound of a particular instrument. Dry curaçao, for instance, was like the clarinet with its shrill, velvety note; kiimmel like the oboe, whose timbre is sonorous and nasal; creme de menthe and anisette like the flute, at one and the same time sweet and poignant, whining and soft. Then, to complete the orchestra, comes kirsch, blowing a wild trumpet blast; gin and whisky, deafening the palate with their harsh outbursts of cornets and trombones; liqueur brandy, blaring with the overwhelming crash of the tubas, while the thunder peals of the cymbals and the big drum, beaten might and main, are reproduced in the mouth by the rakis of Chios and the mastics.

He was convinced too that the same analogy might be pushed yet further, that quartettes of stringed instruments might be contrived to play upon the palatal arch, with the violin represented by old brandy, delicate and heady, biting and clean-toned; with the alto, simulated by rum, more robust, more rumbling, more heavy in tone; with vespetro, long-drawn, pathetic, as sad and tender as a violoncello; with the double-bass, full-bodied, solid and black as a fine, old bitter beer. One might even, if anxious to make a quintette, add yet, another instrument; the harp, mimicked with a sufficiently close approximation by the keen savour, the silvery note, clear and self-sufficing, of dry cumin.

Nay, the similarity went to still greater length, analogies not only of qualities of instruments, but of keys were to be found in the music of liquors; thus, to quote only one example, Benedictine figures, so to speak, the minor key corresponding to the major key of the alcohols which the scores of wine-merchants' price-lists indicate under the name of green Chartreuse.

These assumptions once granted, he had reached a stage, thanks to a long course of erudite experiments, when he could execute on his tongue a succession of voiceless melodies; noiseless funeral marches, solemn and stately; could hear in his mouth solos of creme de menthe, duets of vespetro and rum.

He even succeeded in transferring to his palate selections of real music, following the composer's motif step by step, rendering his thought, his effects, his shades of expression, by combinations and contrasts of allied liquors, by approximations and cunning mixtures of beverages.

Sometimes again, he would compose pieces of his own, would perform pastoral symphonies with the gentle blackcurrent ratafia that set his throat resounding with the mellow notes of warbling nightingales; with the dainty cacao-chouva, that sung sugarsweet madrigals, sentimental ditties like the "Romances d'Estelle"; or the "Ah! vous di-rai-je maman," of former days.But to-night, Des Esseintes had no wish to "taste" the delights of music; he confined himself to sounding one single note on the keyboard of his instrument, filling a tiny cup with genuine Irish whisky and taking it away with him to enjoy at his leisure.

He sank down in his armchair and slowly savoured this fermented spirit of oats and barley-a strongly marked, almost poisonous flavour of creosote diffused itself through his mouth.

Little by little, as he drank, his thoughts followed the impression thus re-awakened on his palate, and stimulated by the suggestive savour of the liquor, were roused by a fatal similarity of taste and smell to recollections half obliterated years ago.

The acrid, carbolic flavour forcibly recalled the very same sensation that had filled his mouth and burned his tongue while the dentists were at work on his gums.In the course of that singular malady which plays such havoc with races of exhausted vitality, sudden intervals of calm succeed the crises. Without being able to explain the reason, Des Esseintes awoke quite strong and well one fine morning; no more hacking cough, no more wedges driven with a hammer into the back of the neck, but an ineffable sensation of well-being and a delightful clearness of brain, while his thoughts became cheerful; and instead of being opaque and dull, grew bright and iridescent, like brilliantly coloured soap bubbles.

This lasted some days; then in a moment, one afternoon, hallucinations of the sense of smell appeared.

His room was strong of frangipane. He looked to see if perhaps there was a bottle of the perfume lying about anywhere uncorked; but there was no such thing in the place. He visited his working-room and then the dining-room; the smell was there too.

He rang for his servant. "Don't you smell something?" he asked, but the man, after sniffing the air, declared he noticed nothing. Doubt was impossible; the nervous derangement was come again, taking the form of a fresh delusion of the senses.

Wearied by the persistency of this imaginary aroma. he resolved to plunge himself in a bath of real perfumes, hoping that his nasal homeopathy might cure him or, at any rate, moderate the force of the overpowering frangipane.

He betook himself to his study. There, beside an ancient font that served him as a wash-hand basin, under a long looking-glass in a frame of wrought iron that held imprisoned like a well-head silvered by the moonlight the pale surface of the mirror, bottles of all sizes and shapes were ranged in rows on ivory shelves. He placed them on a table and divided them into two series; first, the simple perfumes, extracts and distilled waters; secondly, composite scents, such as are described under the generic name of bouquets.

He buried himself in an armchair and began to think. Years ago he had trained himself as an expert in the science of perfumes; he held that the sense of smell was qualified to experience pleasures equal to those pertaining to the ear and the eye, each of the five senses being capable, by dint of a natural aptitude supplemented by an "erudite education, of. receiving novel impressions, magnifying these tenfold, coordinating them, combining them into the whole that constitutes a work of art. It was not, in fact, he argued, more abnormal than an art should exist of disengaging odoriferous fluids than that other arts should whose function is to set up sonorous waves to strike the car or variously coloured rays to impinge on the retina of the eyes; only, just as no one, without a special faculty of intuition developed by study, can distinguish a picture by a great master from a worthless daub, a motif of Beethoven from a tune by Clapisson, so no one, without a preliminary initiation, can avoid confounding at the first sniff a bouquet created by a great artist with a pot-pourri compounded by a manufacturer for sale in grocers' shops and fancy bazaars.

In this art of perfumes, one peculiarity had more than all others fascinated him, viz. the precision with which it can artificially imitate the real article.

Hardly ever, indeed, are scents actually produced from the flowers whose name they bear; the artist who should be bold enough to borrow his element from Nature alone would obtain only a half-and-half-result, unconvincing, lacking in style and elegance, the fact being that the essence obtained by distillation from the flowers themselves could at the best present but a far-off, vulgarized analogy with the real aroma of the living and growing flower, shedding its fragrant effluvia in the open air.

So, with the one exception of the jasmine, which admits of no imitation, no counterfeit, no copy, which refuses even any approximation, all flowers are perfectly represented by combinations of alcoholates and essences, extracting from the model its inmost individuality while adding that something, that heightened tone, that heady savour, that rare touch which makes a work of art.

In one word, in perfumery the artist completes and consummates the original natural odour, which he cuts, so to speak, and mounts as a jeweller improves and brings out the water of a precious stone.

Little by little, the arcana of this art, the most neglected of all, had been revealed to Des Esseintes, who could now decipher its language,– a diction as varied, as subtle as that of literature itself, a style of unprecedented conciseness under its apparent vagueness and uncertainty.

To reach this end, he had, first of all, been obliged to master the grammar, to understand the syntax of odours, to grasp the rules that govern them; then, once familiarized with this dialect, to study and compare the works of the divers masters of the craft, the Atkinsons and Lubins, the Chardins and Violets, the Legrands and Piesses, to analyze the construction of their sentences, to weigh the proportion of their words and the disposition of their periods.

Next, in this idiom of essences, it was for experience to come to the assistance of theories

too often incomplete and commonplace.

The classic art of perfumery was, in truth, little diversified, almost colourless, uniformly run in a mould first shaped by old-world chemists; it was in its dotage, hide-bound in its ancient alembics, when the Romantic epoch dawned and took its part in modifying, in rejuvenating it, in making it more malleable and more supple.

Its history followed step by step that of the French language. The Louis XIII. style, perfumed and full-flavoured, compounded of elements costly at that date, of iris powder, musk, civet, myrtle water, already known by the name of Angels' Water, barely sufficed to express the rude graces, the rather crude tints of the time which certain sonnets of Saint-Amand's have preserved for us. Later on, with the introduction of myrrh, frankincense, the mystic scents, powerful and austere, the pomp and stateliness of the Grand Siècle, the redundancy and artificiality of the orator's art, the full, sustained, wordy style of Bossuet and the great preachers became almost possible; later on again, the well-worn, sophisticated graces of French society under Louis XV found a readier interpretation of their charm in the frangipane and marichale, which offered in their way the very synthesis of the period. Then finally, after the indifference and incuriousness of the First Empire, which used Eau de Cologne and preparations of rosemary to excess, perfumery ran for inspiration, in the train of Victor Hugo and Gautier, to the lands of the sun; it created Oriental essences, selams overpowering with their spicy odours; invented new savours; tried and approved old tones and shades .now rediscovered, which it made more complex, more subtle, more choice; definitely repudiating once for all the voluntary decrepitude to which the art had been reduced by the Malesherbes, the Andrieux, the Baour-Lormians, the vulgar distillers of its poetry.

Nor had the language of perfumes remained stationary since the epoch of 1830. Again it had progressed and following the march of the century had advanced side by side with the other arts. It, too, had complied with the whims of amateurs and artists, flying for motives to China and Japan, inventing scented albums, imitating the flowery nosegays of Takeoka; by a mingling of lavender and clove obtaining the perfume Rondeletia; by a union of patchouli and camphor, the singular aroma of India-ink; by compounding citron, clove and neroli (essence of orange blossoms), the odour, the Hovenia of Japan.

Des Esseintes studied, analyzed the soul of these fluids, expounded these texts; he took a delight, for his own personal satisfaction, in playing the part of psychologist, in unmounting and remounting the machinery of a work, in unscrewing the separate pieces forming the structure of a complex odour, and by long practice of this sort, his sense of smell had arrived at the certainty of an almost infallible touch. Just as a wine-merchant knows the vintage by imbibing single drop; as a hop-dealer, the instant he sniffs at a bag, can there and then name its precise quality and price; as a Chinese trader can declare at once the place of origin of the teas he examines, say on what farms of the Bohea mountains, in what Buddhist Monasteries, each specimen was grown, and the date at which its leaves were gathered, can state precisely the degree of heat used and the effect produced by its contact with plum blossom, with the Aglaia, with the Olea fragrans, with all or any of the perfumes employed to modify its flavour, to give it an added piquancy, to brighten up its rather dry savour with a whiff of fresh and alien flowers; even so could Des Esseintes, by the merest sniff at a scent, detail instantly the doses of its composition, explain the psychology of its blending; all but quote the name of the particular artist who wrote it and impressed on it, the personal mark of his style.

Needless to say, he possessed a collection of all the products used by perfume-makers; he had even some of the true Balm of Mecca, a very great rarity, to be procured only in certain regions of Arabia Petraa and guarded as a monopoly of the Grand Turk.

Seated now in his study at his working table, he was pondering the creation of a new bouquet, aid had reached that moment of hesitation so familiar to authors who, after months of idleness, are preparing to start upon a fresh piece of work.

Like Balzac, who was haunted by an .imperious craving to blacken reams of paper by way of getting his hand in, Des Esseintes felt the necessity of recovering his old cunning by dint of executing some task of minor importance. He determined to make heliotrope, and measured out the proper quantities from phials of almond and vanilla; then he changed his mind and resolved to try sweet-pea.

The phrases, the processes had escaped his memory. So he made experiments. No doubt in the fragrance of that flower, orange blossom was the dominant factor; he tried a number of combinations and ended by getting the right tone by blending the orange with the tuberose and rose, binding the three together with a drop of vanilla.

All his uncertainties vanished; a fever of eagerness stirred him, he was ready to set to work in earnest. He compounded a fresh brew of tea, adding a mixture of cassia and iris; then, sure of himself, he resolved to march boldly forward, to strike a thundering note, the overmastering crash of which should bury the whisper of that insinuating frangipane which still stealthily impregnated the room.